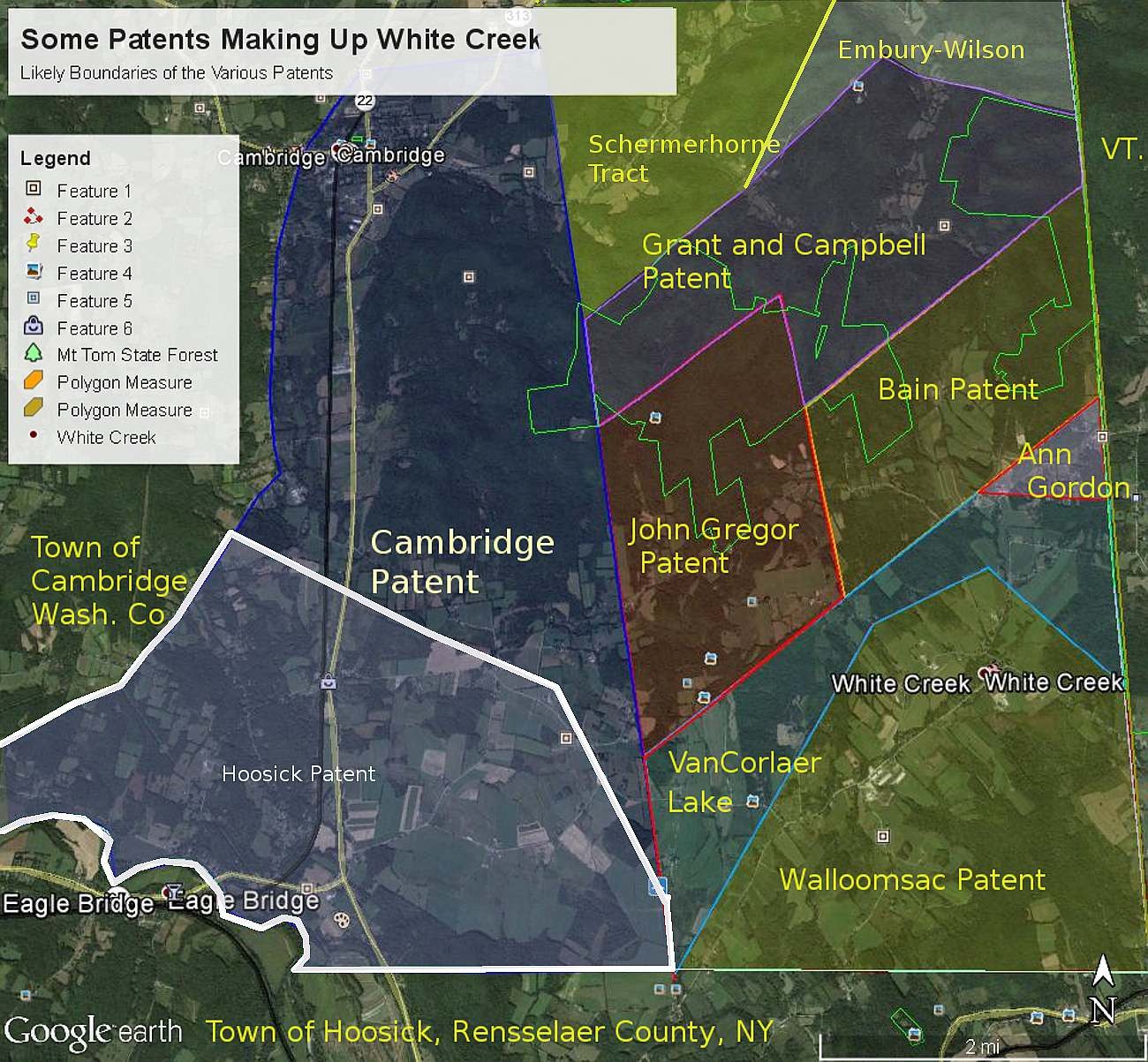

Arent Van Corlaer III kicked things off by establishing a trading post in White Creek in seventeen-eleven, a bold move that laid the groundwork for the town's future. While there's a whisper of settlers possibly being in the area before the Seven Years' War, which ran from 1756-1763, any early folks were likely scared off by the conflict, leaving behind little trace. We don't have names or stories for those fleeting pioneers, but their presence hints at the region's early allure despite its dangers. Once the war wrapped up, the real wave of settlement began. By around seventeen-sixty, the first permanent settlers started trickling in, drawn to the fertile lands and promise of opportunity. Then, around seventeen-sixty-five, it was like someone opened the floodgates—people poured into White Creek, snapping up land in the various patents that carved up the area. These weren't just random plots; we're talking about the Hoosick, Walloomsac, and Cambridge Patents, which were the hot spots early on. Later, folks spread into the Van Corlaer Patent and then the military patents—Gregor, Bain, Gordon, and Grant-and-Campbell. The Embury-Wilson and Schermerhorne Patents? Well, their boundaries are still a bit fuzzy, not quite pinned down with full accuracy yet. Now, things weren't exactly peaceful. The border between New York and the New Hampshire Grants—what we now call Vermont—was a mess during this period. Both sides claimed the same land, and it sparked near-open warfare. Picture heated disputes, maybe even some fistfights or worse, as settlers and officials argued over who owned what. This wasn't just paperwork drama; it shaped how communities formed, with settlers picking sides or just trying to survive the chaos.

After that initial wave hit the Hoosick, Walloomsac, and Cambridge Patents around seventeen-sixty-five, the area really started to take shape. These patents were like the beating heart of White Creek—rich, fertile land that pulled in families ready to carve out a life. The Hoosick Patent, for instance, was a big draw because of its access to the Hoosic River, perfect for farming and small mills. Picture families like the Browns or the Thompsons—names you might find in old deeds—building rough-hewn cabins, clearing dense forests, and planting crops like corn and rye. The Walloomsac Patent, a bit wilder, attracted hardy folks willing to tame its rugged terrain, while the Cambridge Patent became a hub for community-minded settlers who started laying out rough roads and meeting spots. Now, Van Corlaer's trading post wasn't just a pit stop; it was the lifeblood of early White Creek. By seventeen-eleven, it was the go-to spot for trading furs with local Native Americans, swapping goods like iron tools or cloth, and getting news from far-off Albany or even Boston. That border dispute with the New Hampshire Grants? Oh, it was a proper mess. From the seventeen-sixties into the seventeen-seventies, New York and what would become Vermont were locked in a tug-of-war over land claims. Settlers in White Creek often found themselves caught in the middle—some held New York patents, others had grants from New Hampshire, and both sides thought they were right. This led to standoffs, with groups like the Green Mountain Boys, led by fiery Ethan Allen, stirring up trouble. There were tales of land being claimed twice, settlers being evicted, and even barns burned in the worst cases. In White Creek, this chaos meant some folks hesitated to build permanent homes until the dust settled, while others doubled down, forming tight-knit communities to protect their claims. The later military patents—Gregor, Bain, Gordon, and Grant-and-Campbell—came into play as rewards for soldiers from the Seven Years' War. These were often snapped up by veterans or their families, adding a new layer of settlers by the seventeen-seventies. Think grizzled ex-soldiers, maybe a guy named John Gregor or James Bain, swapping war stories while plowing fields. The Embury-Wilson and Schermerhorne Patents, though less clear in their boundaries, likely pulled in Dutch and English families, given the names—Schermerhorne screams Dutch influence from the Hudson Valley.

Picture seventeen-eleven White Creek, where Arent Van Corlaer's trading post stands as the beating heart of a wild frontier. It's a sturdy log structure, smoke curling from a stone chimney, surrounded by a clearing where settlers, Native Americans, and traders mingle. The air hums with the clink of metal tools, the rustle of furs, and voices haggling in Dutch, English, and local languages. A farmer like Thomas Hayworth might haul in a stack of beaver pelts, swapping them for an axe or a sack of flour, while a Mohawk trader inspects iron pots with a keen eye. Women, maybe a Sarah Greene in a homespun dress, barter eggs for needles, chatting about crop yields or rumors of border trouble. The post isn't just about trade—it's a social hub where news from Albany trickles in, like word of the latest New York-Vermont land spat. Kids dart around, dodging barrels, while grizzled trappers share tales of panther sightings over a mug of cider. It's chaotic, lively, and smells of pine, sweat, and smoked meat—a place where White Creek's earliest settlers built not just a living but a community.

So, to wrap up, those early days after seventeen-sixty saw White Creek transform from a contested frontier into a thriving patchwork of farms and families. From the Hoosick to the military patents, settlers braved border wars, harsh winters, and untamed land, with Van Corlaer's trading post as their anchor. Though the Embury-Wilson and Schermerhorne boundaries remain a bit murky, the spirit of those pioneers—shaped by grit, trade, and neighborly bonds—laid the foundation for White Creek's story.

Add Row

Add Row  Add

Add

Write A Comment